Written by Lucia Nalbandian, University of Toronto and Nick Dreher, Toronto Metropolitan University. Photo credit THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nathan Denette. Originally published in The Conversation.

People walk through Pearson International Airport in Toronto in March 2020.

The first interaction many Canadians have with government services today is digital. Older Canadians turn to the internet to understand how to file for Old Age Security or track down a customer service phone number. Parents visit school district websites for information on school closures, schedules and curricula.

These digital offerings present an opportunity to enhance the quality of services and improve citizens’ experiences by taking a human-centred design approach.

Our research has revealed that governments across the globe are increasingly leveraging technology in immigration and integration processes. As Canadian government services focus on improving the experience of their citizens, efforts should be extended to future citizens as well.

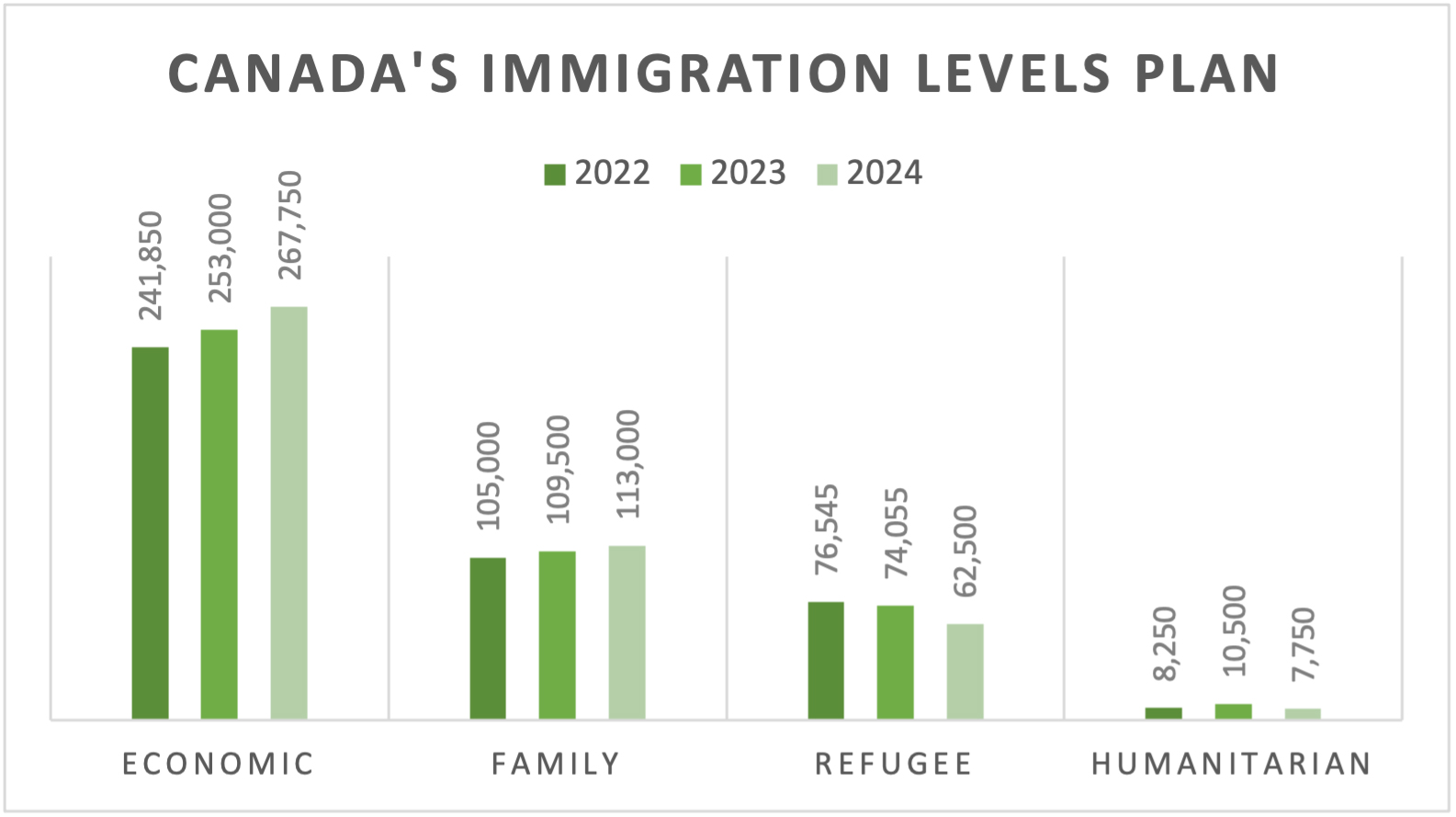

Immigrants are a vital part of the Canadian economy and social fabric. In announcing Canada’s new immigration target of 500,000 permanent residents per year by 2025, Immigration Minister Sean Fraser said the numbers strike a balance between our economic needs and international obligations.

Despite the importance of immigrants for the Canadian economy and national identity, it remains to be seen if immigrants are engaged in the development of policies, services and technological tools that impact them.

Advancements in the immigration sector

Canada has steadily been introducing digital technologies into services, programs and processes that impact migrants. This has especially been the case with the COVID-19 pandemic requiring organizations to innovate their services and programs without diminishing the overall quality of service.

Immigration scholar Maggie Perzyna developed the COVID-19 Immigration Policy Tracker to examine how the Immigration and Refugee Board and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) used digital tools to enable employees to work from home. This helped reduce the administrative burden and increased efficiency.

There continues to be a strong case for technological transformation in Canada’s immigration-focused departments, programs and services. As of July 31, 2022, Canada has a backlog of 2.4 million immigration applications.

In other words, Canada is failing to meet the application processing timelines it has set for itself for services —including passport renewal, refugee travel documents, and work and study permits.

While the Canadian government is trying to address these backlogs, there appears to be no discussion of asking immigrants about their journey through the application process. Rather, the government appears to centre employees. Still, issues with the Global Case Management System persist, driving current case management system issues for employees and government service users.

Virtual processes were prioritized

While the Canadian government previously introduced a machine learning pilot tool to sort through temporary resident visa applications, its use stagnated due to pandemic-related border closures. Instead, virtual processes and digitization were prioritized, including:

- Shifting from paper to digitized applications for the following: spousal and economic class immigration, applicants to the Non-Express Entry Provincial Nominee Program, the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot, the Agri-Food Pilot, the Atlantic Immigration Pilot, the Québec Selected Investor Program, the Québec Entrepreneur Program, the Québec Self-Employed Persons Program and protected persons.

- Hosting digital hearings for spousal immigration applicants, pre-removal risk assessments and refugees using video-conferencing.

- Introducing secure document exchanges and the ability to view case information across various immigration streams.

- Offering virtual citizenship tests and citizenship ceremonies.

Additionally, Fraser announced further measures to improve the user experience, modernize the immigration system and address challenges faced by people using IRCC. This strategy will also involve using data analytics to aid officers in sorting and processing visitor visa applications.

These changes showcase Canada’s efforts to pair existing challenges with existing solutions — initiatives that require relatively low effort. Yet while these digitization efforts streamline administrative processes and reduce administrative burden, application backlogs persist.

While useful, these initiatives focus on efficiencies in IRCC processing for employees. As IRCC evaluates and develops processes, it should prioritize the experience of end users by taking a migrant-centred design approach.

The value of human-centred design

Human-centred design is the practice of putting real people at the centre of any development process, including for programs, policies or technology. It places the end user at the forefront of development so user needs and preferences are considered each step of the way.

To maximize value in technology implementation, IRCC should take a migrant-centred design approach: apply human-centred design principles with migrants treated as the end users. This approach should consider the following suggestions:

- Centre migrants in the development of immigration programs, policies and services, and digital and technological tools by seeking migrants’ input in forthcoming and proposed changes.

- Take a life-course approach to human and social service delivery by recognizing that “all stages of a person’s life are intricately intertwined with each other.” Government services prioritize Canadian citizens, but a life-course approach understands that all individuals in Canada, regardless of their current immigration status, represent potential Canadian citizens. Government services should implement a life-course approach by prioritizing quality services for migrants, some of which are seniors that will require different government services in the future.

- Combat discrimination and bias in developing new immigration technology tools. Artificial intelligence and other advanced digital technologies have the capacity to reproduce biases and discrimination that currently exist in IRCC. Any new technologies must be evaluated to prevent discrimination or bias.

As Canada continues to explore how technology can help streamline and improve the migrant journey, migrant-centred design should be at the forefront of their planning. When we design processes, policies and tools with intended users at the centre, they are more likely to resonate with users.

If Canada wants to be a first-choice migration destination, we need to approach immigration policies — including technology use — as opportunities to empower and encourage migrants.