Written by , Ryerson University. Photo credit: (Philip Share/Craig Jennex), Author provided (no reuse). Originally published in The Conversation.![]()

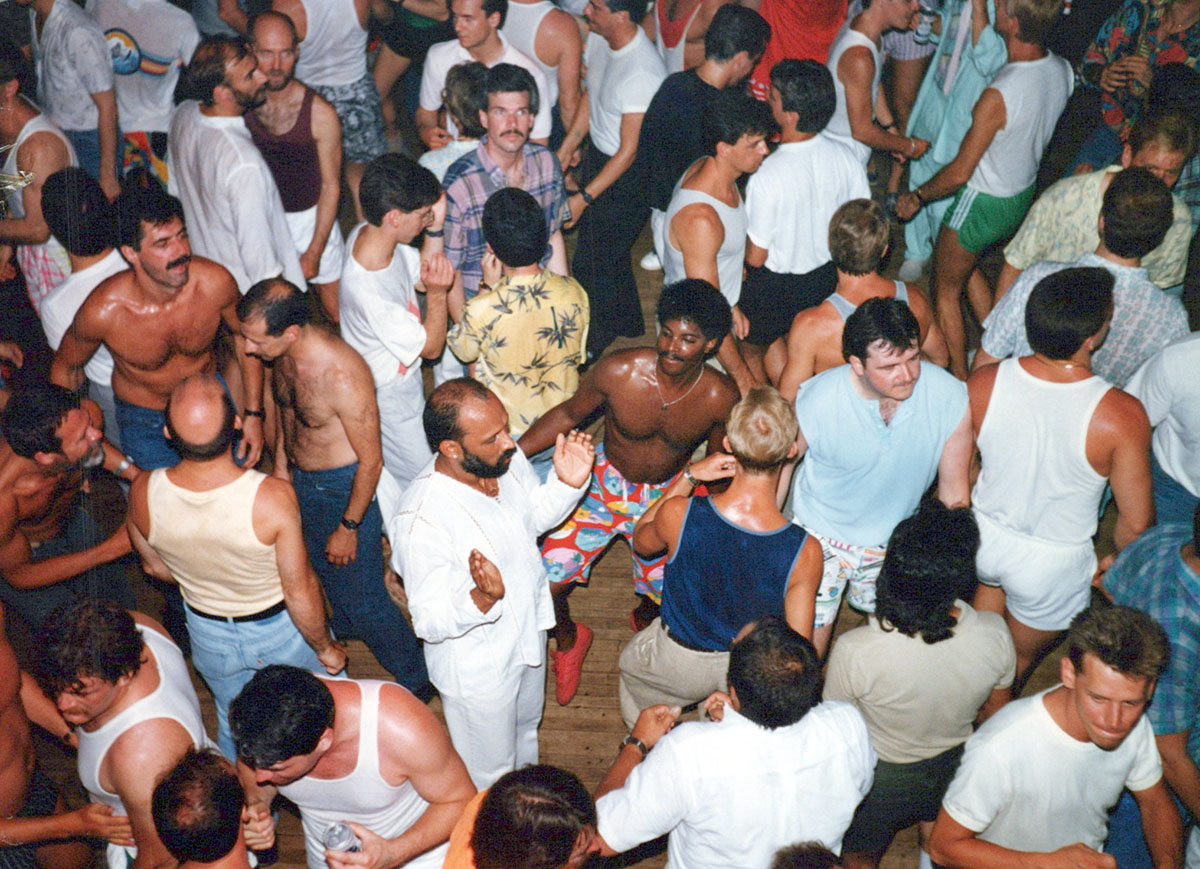

The dance floor was a place of belonging in the face of homophobic violence, the HIV/AIDS epidemic and moralistic representations of gay life.

As we dream of the lives we might once live again when the COVID-19 pandemic wanes, I find myself most excited about potential experiences of collective effervescence — the hopeful feelings that arise from a shared sense of belonging with others.

Having kept our distance over the last two years to keep each other safe, these spontaneous moments of communal joy have been difficult to find. Virtual events (including some hugely popular queer dance parties) have emerged, born out of the desire to connect and move together. While these are meaningful ways to stay tethered to social communities, they fall short of the powerful feelings that require physical proximity.

Alongside a team of undergraduate and graduate students at X University in Toronto, I’ve spent the last year exploring the work of the Gay Community Dance Committee (GCDC), a volunteer organization that hosted dance parties in Toronto from 1981 to 1992.

This research has not only connected us with this community across time and space, but has also reminded us of the transformative possibilities of meeting strangers on the dance floor. As the research team imagines a future full of safe and meaningful experiences of public kinship, we have been inspired by LGBTQ2+ social organizing in the past.

How dance parties funded liberation

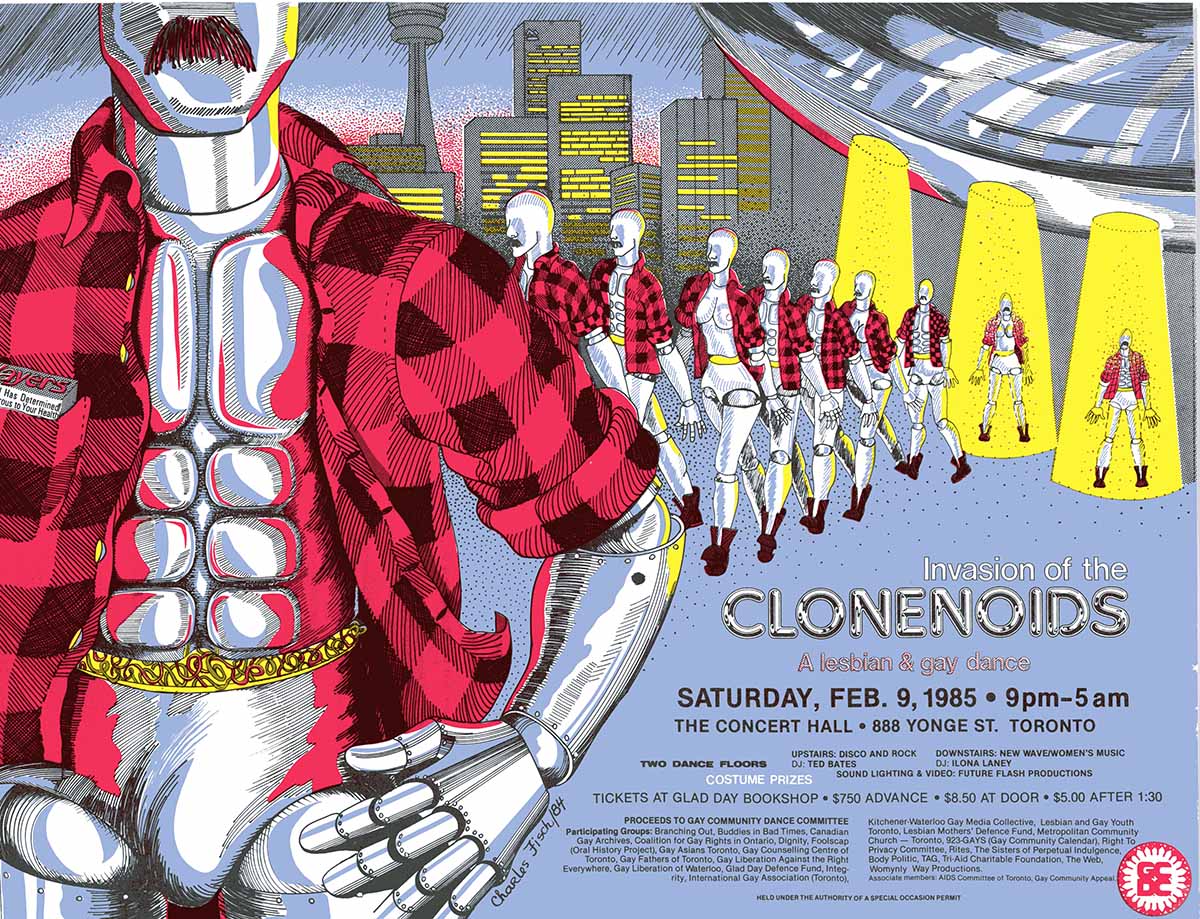

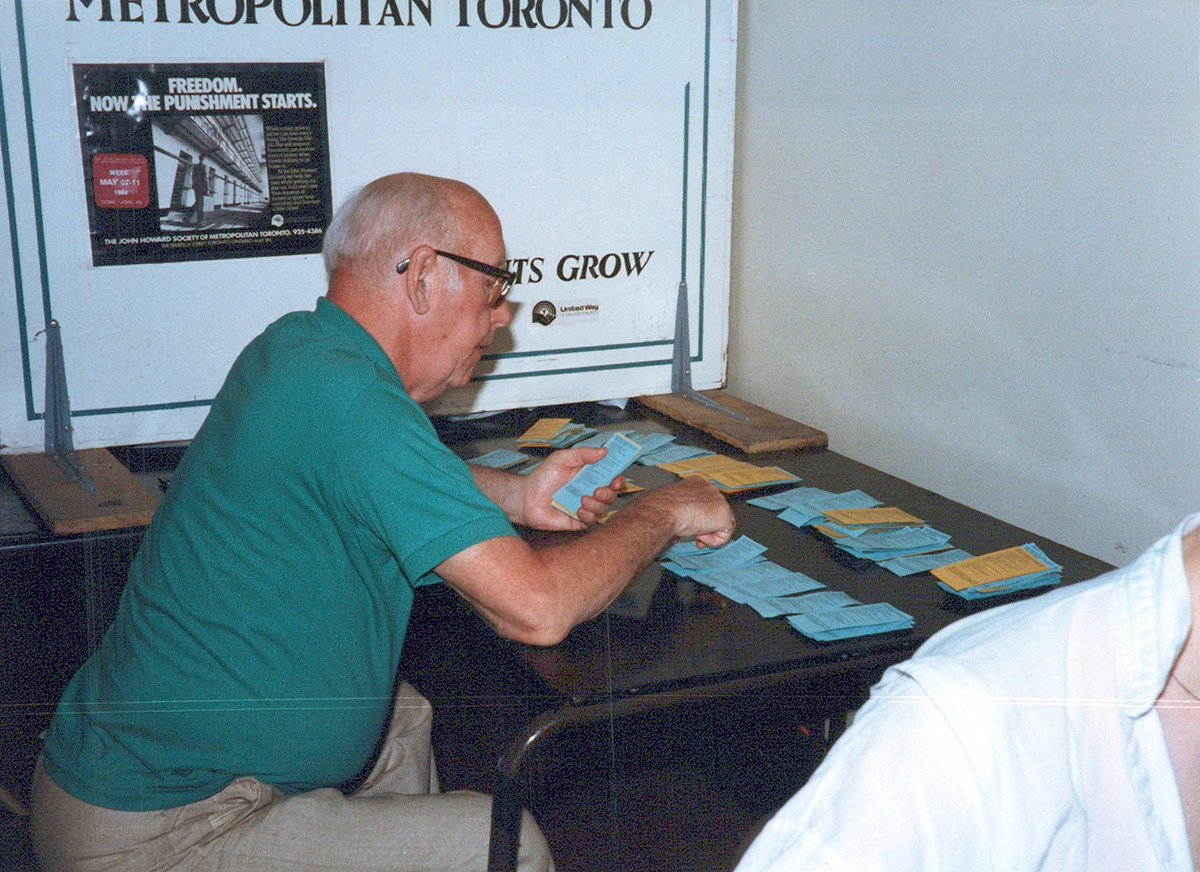

The GCDC formed in 1981. Its aim was to encourage and sustain collaborations between diverse community groups in the Greater Toronto Area, organize community-oriented dances and divide proceeds among participating organizations based on their volunteer hours and ticket sales.

An executive committee oversaw the logistics, provided administrative continuity between dances and supported participating organizations. Together, the committee hosted large-scale events for thousands of participants that would have been impossible for any one group to convene alone.

During its nearly 12-year tenure, the GCDC raised over $250,000 to support the work of the AIDS Committee of Toronto, Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, the Canadian Gay Archives (now The ArQuives), Gays and Lesbians of the First Nations of Toronto (now 2 Spirited People of the First Nations), Lesbian Mothers’ Defence Fund, The Body Politic (a gay and lesbian magazine) and ZAMI (one of the first organizations in Canada specifically for lesbian and gay people of colour).

Solidarity in a lean and mean era

Funding from these dances allowed groups to sustain their work during the 1980s.

This was a decade of neoliberal reorganization that emphasized individual responsibility, saw the privatization of public goods and services and valued competition over collective good. Community organizers I interviewed remembered the 1980s as an unkind era that made community work not only difficult, but increasingly necessary.

However, the GCDC’s role in lesbian and gay liberation history was greater than financial support. During a decade when lesbian and gay communities experienced substantial harm in the forms of homophobic violence, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, moralistic representations of gay life and government agencies that were dismissive or explicitly hostile, the group allowed LGBTQ2+ people to recognize a shared belonging and power.

The GCDC created opportunities for open, shifting and heterogeneous collectives of queer people to come together and experience bliss in a cultural moment when collective joy with strangers often seemed unlikely, or even impossible.

Beyond fundraising, GCDC’s dances enabled participants to feel a sense of belonging and political power in the face of devastation, isolation and illness.

How dance transforms

Collective dance has been a cornerstone of queer community building for generations. Some of the clearest examples exist in disco cultures, ballroom scenes and womyn’s music festivals.

It’s no coincidence that the most famous riot in queer history took place at The Stonewall Inn, one of the few gay bars in New York City that allowed same-sex dancing to soul and funk music — genres that embody experiences of rhythm and groove and feelings of being in the moment, collectively, on the dance floor.

Similarly, the GCDC’s dance floor was an opportunity to experience, for a brief moment, a sense of freedom, belonging, safety and agency that was often difficult to find.

When I interviewed community archivist Alan Miller, he said “during the AIDS crisis, everything was falling apart around us. The dances offered relief. A chance to just enjoy yourself for a little while.”

Deb Parent, a lesbian activist and regular DJ at GCDC dances, explained that moments on the queer dance floor are important because they are “moments when we are safe and free. We can imagine: What if this was our life? What if we could live all of our lives from this place without having to think through the danger or the consequences without being told what we can or can’t do, how we should or shouldn’t dress, who we should or shouldn’t love.”

GCDC dances enabled people to perceive the sheer size and scope of the city’s lesbian and gay liberation projects — as well as their place within it.

While the vast majority of volunteers joined the GCDC because of their close association with a particular community organization, their allegiances within the GCDC structure were often “fleeting,” according to former GCDC volunteer Ron Merko.

Merko explained that many people who signed up as volunteers representing one organization regularly changed their affiliation and gave volunteer labour hours to different groups (like the AIDS Committee of Toronto) that were in particular need of funding.

In promoting joy between people and and mutual support among queer organizations, the GCDC promoted both coalition-building and liberation. It prioritized the dance floor as a site of collective belonging and communal care where queer people could imagine radically different worlds, and intervene in a troubling present to work toward a better future.

How we return

In our contemporary moment, when some well-funded LGBTQ2+ organizations seemingly move further away from the communities they claim to represent and society prepares to return to collective experiences with friends and strangers, those of us in queer communities should recall the grassroots, pleasurable and collaborative work of the GCDC — and the political possibilities that exist in its wake.

As I’ve learned through researching and writing on the queer past, in particularly difficult present realities, there are often exciting and hopeful possibilities shining brightly in the past.