LGBTQ+ organizations in Canada are gearing up for a “Rainbow Week of Action” that will feature rallies across the country calling on governments to do more to support LGBTQ+ communities.

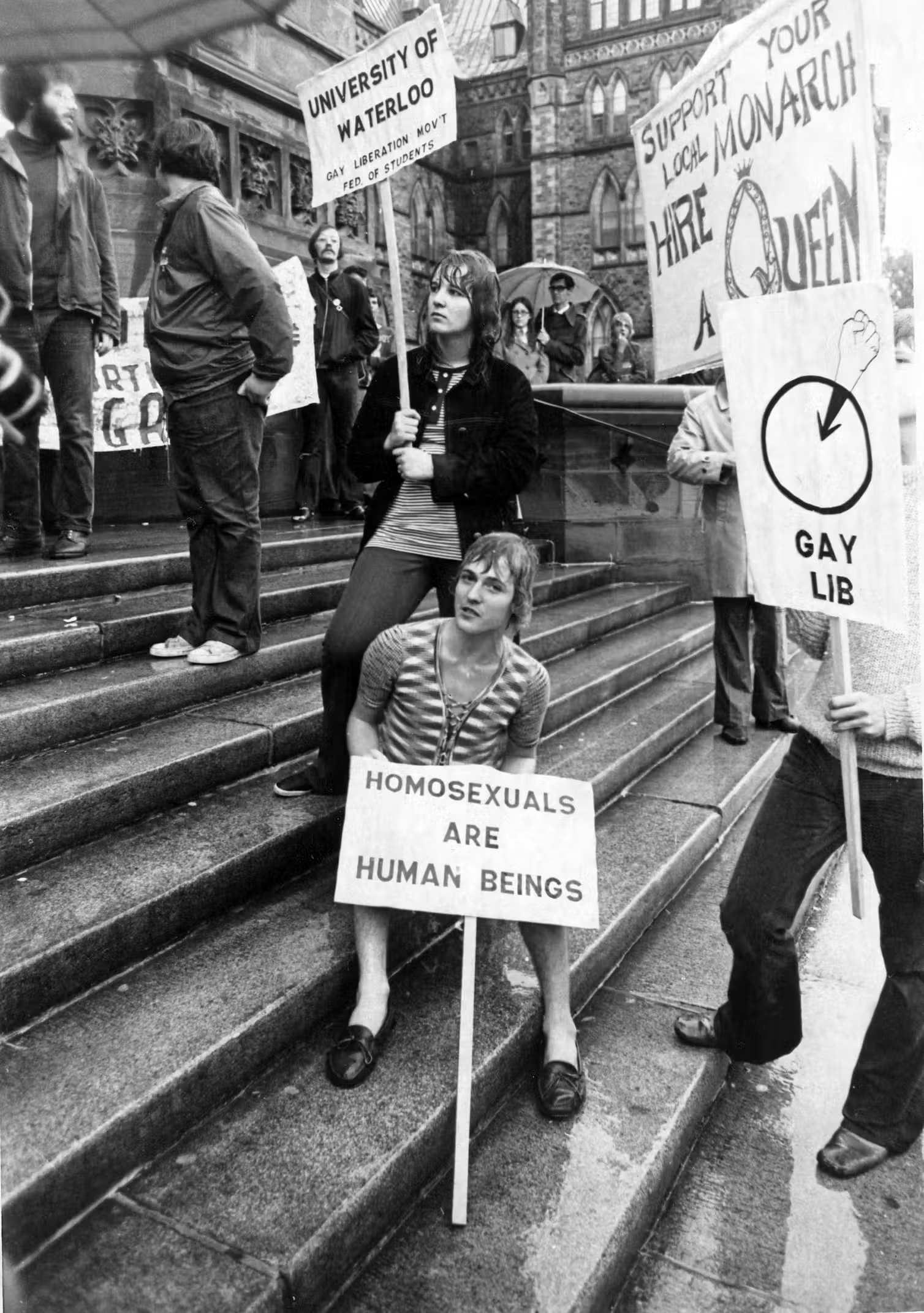

Such events are part of a long history of LGBTQ+ campaigning and protest. However, in a time when anti-LGBTQ+ movements are growing, recording that history is as important as ever.

As increasingly advanced digital technologies pervade every aspect of our lives, making that history easily accessible online can help contemporary movements learn from previous generations of activists.

At the Lesbian and Gay Liberation in Canada project (LGLC), we are aiming to learn from lesbian activists of the past to uncover which of their practices can inform the creation of online history resources today.

Our project, working alongside the University of Ottawa’s Digital Humanities Lab and Toronto Metropolitan University Libraries’ Collaboratory, highlights how feminist and queer practices can create meaningful change using digital methods and tools.

Recording Canadian LGBTQ+ history

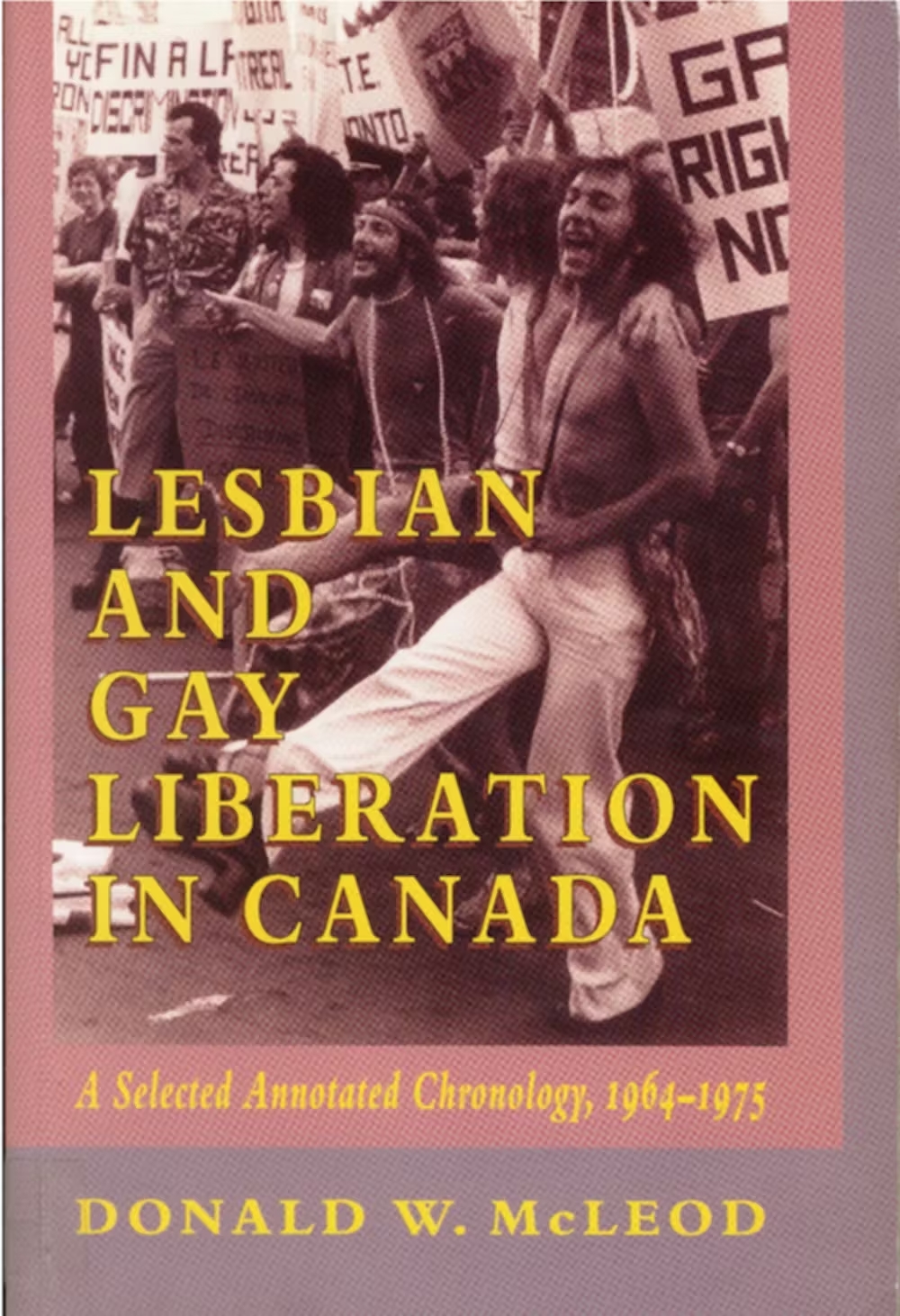

The LGLC project was developed from author Donald McLeod’s two print chronologies, Lesbian and Gay Liberation in Canada, which span from the start of the first homophile association in Vancouver in 1964 to the start of the AIDS crisis in 1981.

A longstanding volunteer at ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives, McLeod began work on his chronologies in the early 1990s after discovering visitors to the ArQuives knew very little about gay and lesbian history, especially within Canada.

The LGLC project aims to further McLeod’s goal of engaging contemporary readers in Canadian LGBTQ+ history by moving into the digital sphere. Since 2011, we have been working to expand the text and related resources online, moving from McLeod’s 3,200 event listings to 34,000 records about the events, places, people, organizations and print publications that formed the movement.

Making this material accessible digitally allows for a more interactive and engaging exploration of LGBTQ+ Canadian history. It enables users to easily move through time and geography, and to understand the interconnectivity of events and figures within the gay liberation movement — something that is not as feasible in a book format.

We’ve extended the end date for our historical research to 1985, when Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms came into effect. It stipulates that every individual is equal under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination.

Users are able to see how the movement was formed and evolved over time; how its ideas moved between cities and beyond well-defined societal and political identities; and how liberation activists survived — and won — many battles because of the links that connect people through their shared oppression.

In an age where it is clear that hard-won rights can be eroded, projects like the LGLC help to ensure that rights movements are preserved against the loss of collective memory.

Wages Due Lesbians

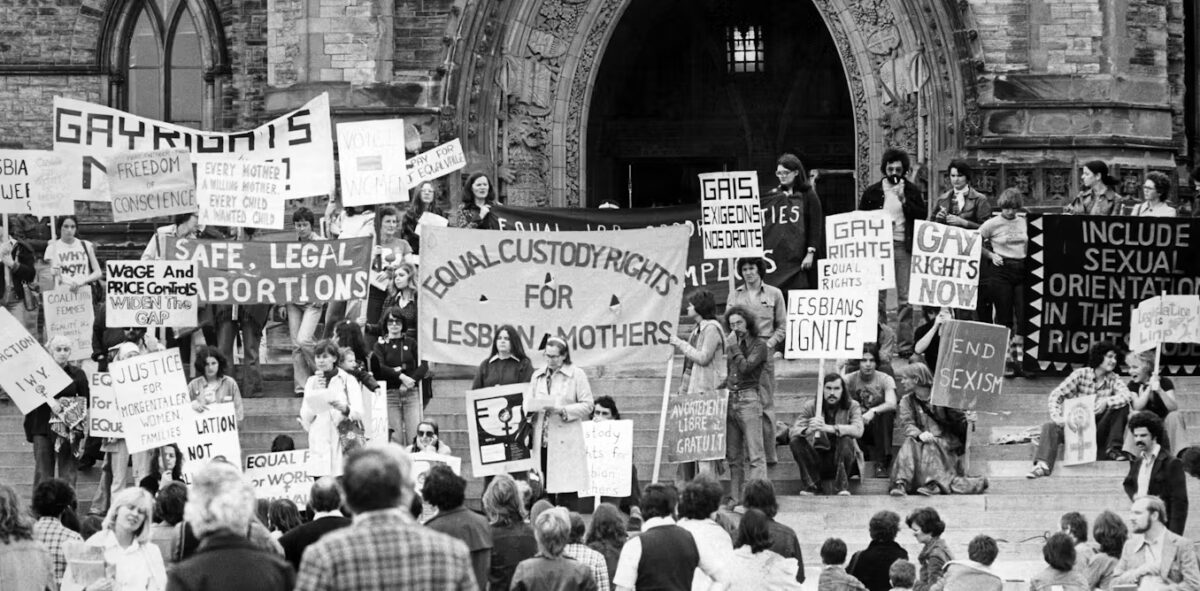

One such organization LGLC has been able to spotlight is Wages Due Lesbians, which was an extension of the Wages for Housework movement of the 1970s. The movement sought to ensure the financial security of women who worked within the home, and who created the Lesbian Mothers Defense Fund, in support of custody rights for lesbian mothers.

Wages Due Lesbians argued that lesbians should be recognized as full citizens despite many of them not contributing reproductive work to the capitalist patriarchal system in Canada. Since women’s value was often associated with their productive and reproductive capacities, Wages Due Lesbians argued that heteronormativity rendered lesbians’ work undervalued and underpaid.

Wages Due Lesbians focused on a discourse of shared oppression, shared goals and shared needs. They organized women’s dances, rallies, meetings and launched a bookmobile to reach rural areas and the Child Custody Fund to support lesbian mothers fighting for the custody of their children.

They were famous for the subversive song “Fucking is work” which shone a light on the undervalued emotional and physical labour of love and support.

Keeping queer history alive

Our access to this activist history depends on archives that have defied the tradition of collecting material valourized by patriarchy. As American poet and essayist Adrienne Rich aptly put it, archiving is an act of survival, a means of understanding and sharing information about the implicit and explicit assumptions in which women are immersed and an act of refusing to be destroyed by patriarchal society.

The researchers that lead and support the LGLC project work hard to seek out events that have yet to be shared online by sifting through boxes of archived material. No voice is excluded from the encoding project: we have found workaround for anonymous voices to be included in the database, and we employ date tagging that allows for uncertain dates.

We collaborate with other organizations including the Quebec Lesbian Network, Wikimedia Canada and the Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities. We share our work through the website, but also through open data, Wikipedia edit-a-thons, teaching material, movie nights and volunteering at public-facing events.

It is important to keep queer history alive so the nuance, wrongs and the triumphs of the past are not lost, and so the work of previous generations is recognized and valued.

It also helps us to recognize how much feminist and queer organizing of the 1970s often excluded trans and racialized people. The LGLC strives to not ignore or whitewash the histories and legacies of anti-trans, racist and colonial violence and legislation and their effects.

While many white cisgendered Canadians continue to benefit from this history today, the history of LGBTQ+ and feminist organizing teaches us that renewed violence and legislative turns threaten bodily autonomy of all Canadians.

Through the LGLC project we hope to contribute to safeguarding the legacies of past movements and empower current and future activists. By embracing new technologies and practices, we can ensure the histories of marginalized communities are not only remembered but remain catalysts for change.