Category Justice, Equity & Society

Increasingly, democratic states and institutions are facing a combination of external and internal challenges. These challenges, impacts, and intersections are taken up by our faculty.

Homestays can help refugee women get to grips with life in a new country

Black-affirming campus spaces are vital for Black student academic success

Canada needs a focused and flexible foreign policy after years of inconsistency

How rich philanthropists exert undue influence over pro-Palestinian activism at universities

Trump found guilty in hush money trial, but will it hurt him in the polls? Here’s why voters often overlook the ethical failings of politicians

Women’s sports are thriving in Canada — here’s how to ensure it stays that way

Banning offenders from changing their names doesn’t make us safer

Controversial ‘Steal from Loblaws Day’ is not just illegal — it won’t foster meaningful change

How a digital archive is preserving Canada’s history of LGBTQ+ activism

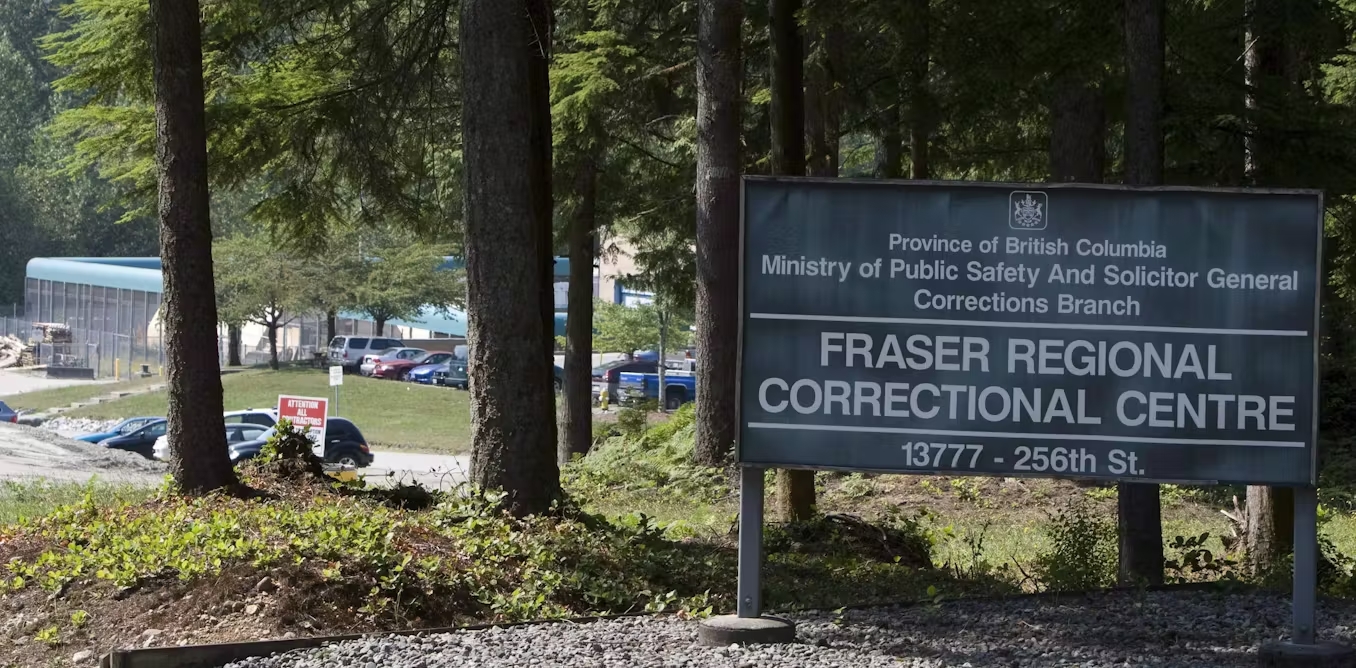

Detaining migrants in prisons violates human rights and risks abuses