Category Health & Well-Being

TMU approaches health and well-being research by focusing on quality of life and promoting well-being for all.

How game worlds are helping health-care workers practise compassionate clinical responses

The power of belief: How expectations influence workplace well-being interventions

The health-care crisis won’t be solved without addressing the elephant in the room: Staff workload

Detoxifying masculinity: How men’s groups reshape attitudes

Striving for transparency: Why Canada’s pesticide regulations need an overhaul

Detangling the roots and health risks of hair relaxers – Listen, with Cheryl Thompson

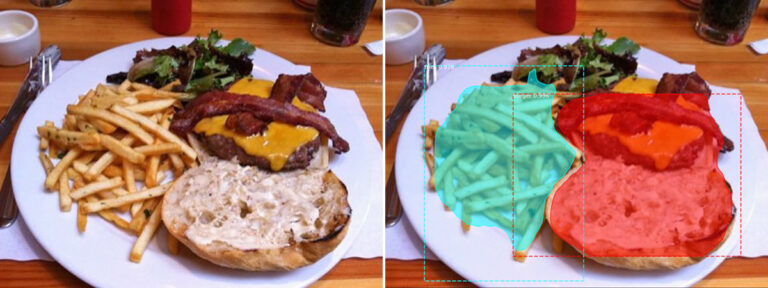

Counting carbs with AI for real-time glucose monitoring

Smart wearables that measure sweat provide continuous glucose monitoring

Food for thought: How your mindset can make healthy food more alluring on social media

Lowering carbon emissions by optimizing energy retrofits