Written by , Toronto Metropolitan University. Photo credit Nariman El-Mofty/AP Photo. Originally published in The Conversation.

Rescue workers stand on the rubble following a Russian rocket attack on a residential apartment block, in Chasiv Yar, Donetsk region, eastern Ukraine on July 10, 2022.

Those on the left of the political spectrum are floundering over what to say about the war in Ukraine.

Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro supports Russia’s Vladimir Putin, who has been his ally since 2018.

Socialists have denounced high-profile American leftists Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders for backing the United States. Fightback, the Canadian section of the International Marxist Tendency, supports neither Ukraine nor Russia, declaring this a “reactionary war on both sides.”

The leading radical-left magazine in the United States, Jacobin, tries to have its cake and eat it too, issuing moral condemnations of Russian aggression (the left’s equivalent of “thoughts and prayers”) while opposing actual material support for Ukraine.

Renowned linguist and anti-war activist Noam Chomsky is, as always, focusing on the harms of American imperialism to the exclusion of almost every other consideration.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian intellectuals, socialists and even anarchists have chided the North American left for its lack of a coherent solidarity with Ukrainians.

The reason for this floundering is simple: supporting military aid to Ukraine involves siding with U.S. imperialism, but opposing military aid means condoning Russian imperialism and probable genocide in Ukraine.

Much is made of the need for a diplomatic solution, potentially involving Ukrainian neutrality. But Ukraine requires foreign aid to defend itself militarily, and Russia has no incentive to accept a diplomatic solution or to honour it down the road.

The left seems to be trapped in a no-win situation, ideologically speaking. There is no morally pure position to take.

To climb out of this trap, the left needs to move beyond the notion of good versus evil and similar moral binaries while shifting its focus to the economic issues at the root of the crisis.

Good Ukraine vs. evil Russia?

The dominant media narrative in the West is one of a heroic Ukraine and its allies fighting virtuously against a villainous Russia. There are obvious facts that support this narrative: Ukraine is a liberal-democratic country with an elected Jewish president; Russia is a fascist dictatorship committing a war of aggression and war crimes.

But some facts don’t fit this narrative. Ukraine has a strong fascist movement itself, which has played an influential role in its antagonism with Russia.

Since 2015, the Ukrainian government has restricted Russian-language rights while also committing human rights abuses in the Donbas. Black and brown Ukrainian residents have suffered severe discrimination during this crisis.

Meanwhile, western media coverage of Ukraine’s plight has been much greater and more sympathetic than its coverage of non-white countries, and sometimes overtly racist, revealing how Ukraine benefits from white privilege in international relations.

And of course the United States, Ukraine’s main ally in this war, is the most dominant imperial power in the world, with a long history of subverting democracy, supporting authoritarianism and abetting or committing genocide.

U.S. support for Ukraine certainly could have more to do with its pursuit of geopolitical power than with democratic values.

Good Russia vs. evil West?

Given these facts, it’s tempting, as some have done, to position Russia as merely defending itself against the U.S., imperialist aggression. But this narrative also ignores important facts.

Russia is a regional power with its own long history of imperialism and genocide, including the deliberate suppression of Ukrainian culture, the artificial famines of 1932-33, the ethnic cleansing of Crimean Tatars in 1944, and, more recently, war crimes during the first and second Chechen wars.

Putin’s government has denied the existence of Ukraine as a nation and has called for a violent “de-Nazification” of Ukraine that clearly amounts to a program of cultural erasure.

Russian attacks on civilians and the infrastructure of civilian life have been consistent with genocide as defined in the United Nations genocide convention.

Meanwhile, the Putin government itself is overtly fascist in all but name: an authoritarian state headed by a hyper-masculine strongman, committed to an ideology that is not only ultra-nationalist, supremacist and imperialist but also deeply sexist, homophobic and transphobic.

For these qualities, Putin is admired by the global far right. A Putin victory in Ukraine would likely strengthen fascist movements around the world.

From good vs. evil to changing the system

During the Second World War, Ukraine became a battleground between two genocidal powers. Ukrainians faced impossible dilemmas, made morally compromised choices and suffered horrifically. Today that situation is repeated.

At the moment, western socialists are struggling to articulate a position on the Ukraine war that opposes both fascism and liberalism. This is genuinely difficult. Opposing imperialism, in this instance, requires military and economic support for Ukraine, even if it comes from the U.S. But this is also the liberal position.

What else can socialists bring to the table?

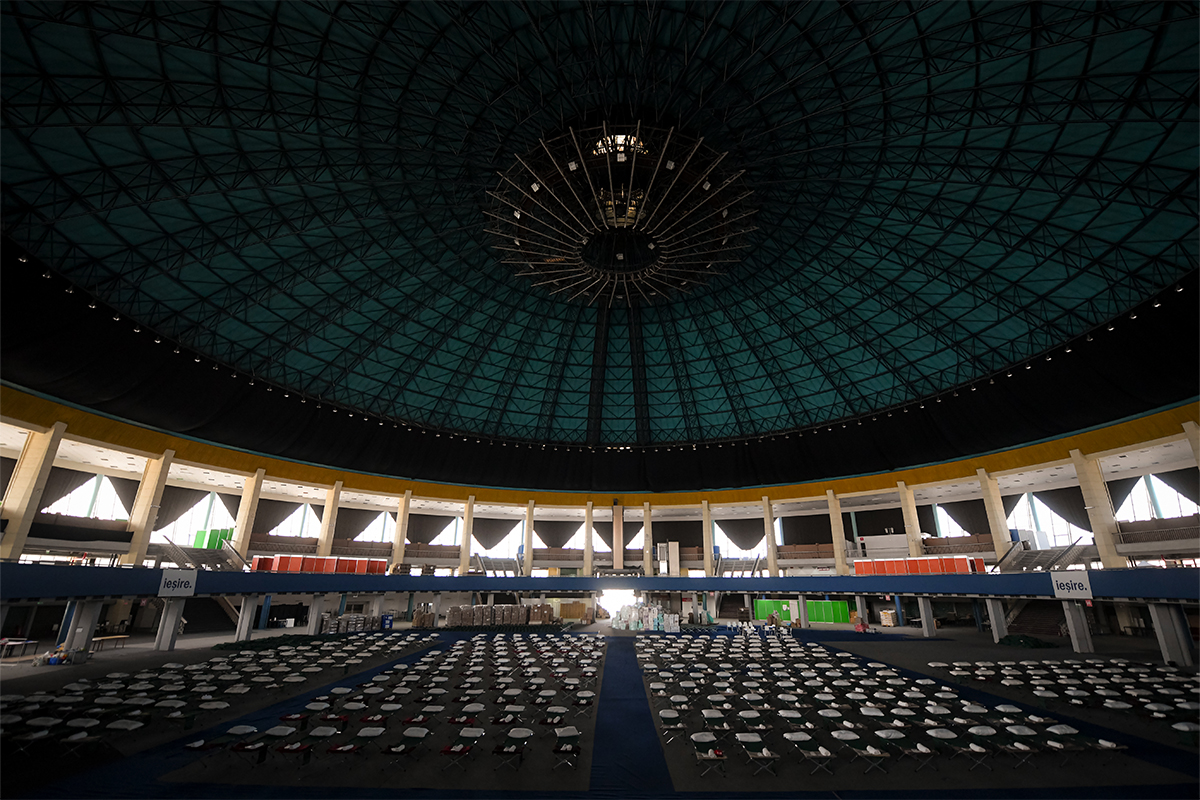

Ukrainian and Russian socialists emphasize the need for economic measures, including humanitarian support for refugees and a cancellation of Ukraine’s foreign debt.

Outside Ukraine, the war is already having global economic impacts, and most likely will exacerbate economic inequality. As with the COVID-19 pandemic and most other disasters, this crisis causes pain for workers while corporations find ways to profit.

Economic inequality is also the root of the war, the enabling condition for Putin’s rise to power and the fuel for the far right in general.

Ending fascism and imperialism for good will require building a more equitable system to replace capitalism. Doing that will require building global networks of solidarity among working people. And doing that requires moving out of good versus evil narratives, in this case by recognizing why Ukrainians actually want western support — and why they should receive it.