Written by Safiyya Hosein, Toronto Metropolitan University. Photo credit: Daniel McFadden/Marvel Studios 2022. Originally published in The Conversation.

Muslim participants of different backgrounds who participated in an audience study said they identify with Kamala Khan, also known as Ms. Marvel, because she’s connected both to her ancestral culture and her American one.

The Disney+ TV show featuring Ms. Marvel, also known as Kamala Khan — the first Muslim superheroine of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), launched June 8 — and the internet has been alight with discussions about the lovable titular character.

The comic book series, Ms. Marvel shot to No. 1 on the comic book charts after its 2014 debut.

The Pakistani American teen Kamala has been one of the most successful characters Marvel unveiled in the past decade, with a large audience reach.

The show has received strong reviews, and Kamala’s representation is a breakthrough — particularly to her South Asian, Muslim and racialized fans.

Unfortunately, the show has also received some racist and sexist backlash in the form of internet “review bombers,” people who spam a show with negative reviews, who are upset with the new identity of Ms. Marvel.

Trailer for ‘Ms. Marvel.’

Regular Pakistani American teen

Kamala, played by Iman Vellani, is a regular Pakistani American Muslim teen who transforms into a superhero. In the comics, this happens after she comes into contact with a mist that induces genetic mutation. In the show, her powers are unlocked after she puts on her grandmother’s bangle.

Viewers can partly credit Ms. Marvel’s success to the comic series’ co-creator and editor, Sana Amanat, a Pakistani American Muslim, and its first writer, G. Willow Wilson, a white American convert to Islam.

Wilson wrote Kamala so beautifully that her struggles appealed to a large audience. As The New Yorker reports, Amanat and Wilson knew that as a breakthrough Muslim superhero, Ms. Marvel would face high expectations: “traditional Muslims might want her to be more modest, and secular Muslims might want her to be less so.”

Their work was also unfolding in the charged post-9/11 climate when representations of Muslims, while gaining some nuance, have also reiterated long-standing orientalist stereotypes — and Islamophobes framed debates that questioned the compatibility of Islam with the West.

South Asian Muslim culture

In both the comic and TV series, Kamala’s representation of Islam is primarily a South Asian one. For instance, Kamala wears a South Asian dupatta, when praying in the mosque. And the inter-generational trauma created by Partition, which led to the creation of the South Asian Muslim state, Pakistan, is a driving force in the plot.

Characters speckle their conversations with phrases and words in Urdu. Episode 1 shows Kamala and her mother shopping for a ceremony that is among the most important events in South Asian backgrounds: a wedding. The event is later shown in Episode 3.

The audience is treated to a fitting of Kamala’s go-to-South Asian wear in this episode, the shawlaar kameeze. In this scene, another major fixture in South Asian culture debuts: The gossiping aunty. South Asian music is also a regular feature on the show, and Marvel has posted links to the soundtracks which include a mix of pop and desi tracks.

Supporting cast: Nani and Red Dagger

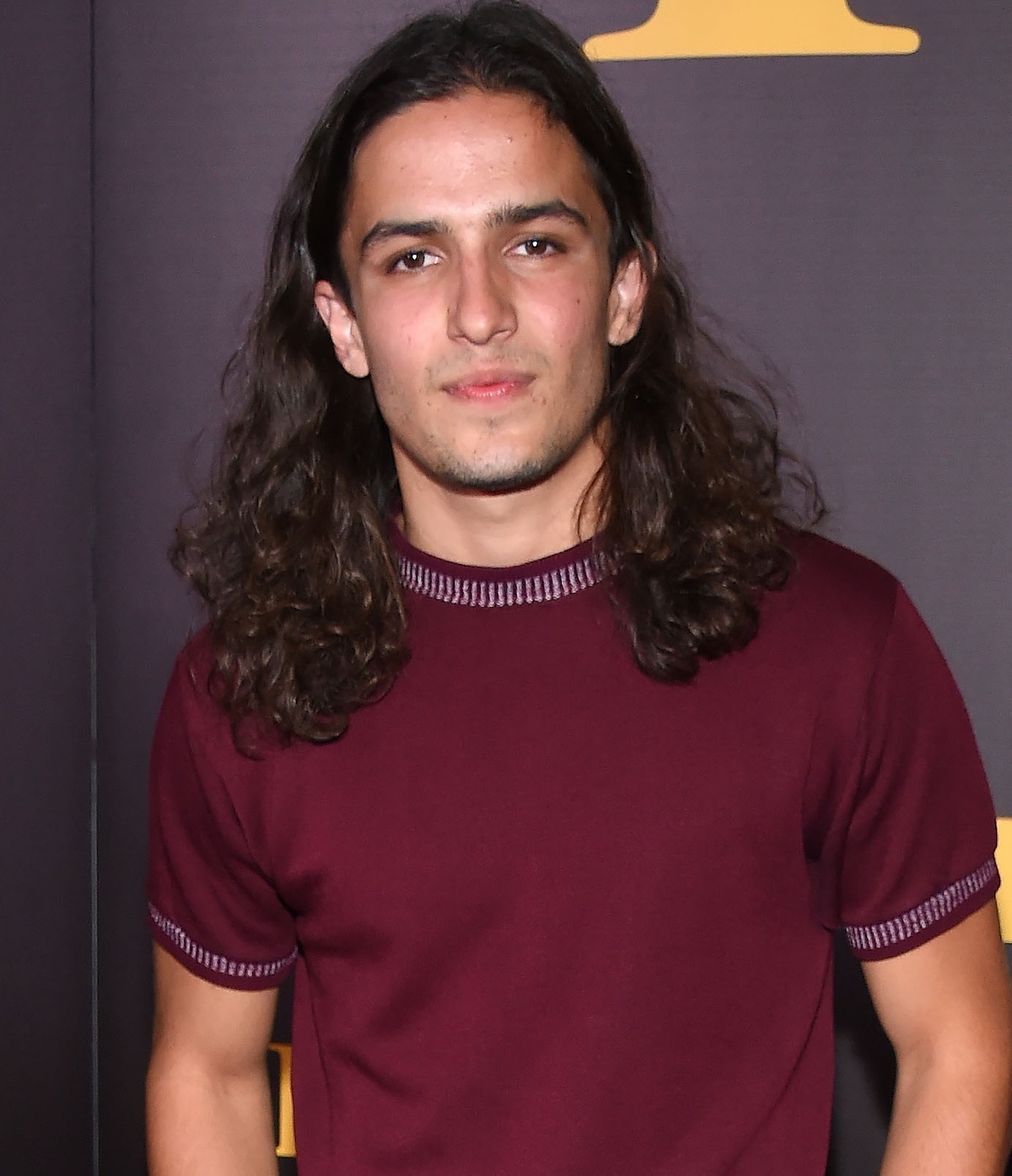

I’m looking forward to the plot lines with two South Asian characters — Kamala’s nani (maternal grandmother), played by Samina Ahmed, and the Pakistani male superhero, the Red Dagger, played by Aramis Knight.

Red Dagger currently stars in a webcomic with Ms. Marvel and is important mainly because western popular media has often depicted Muslim men as oppressors of women, not superheroes.

Breaking the tired tropes

I’m excited about Kamala’s screen debut because of what she signifies to her South Asian, Muslim and racialized female fans after a lifetime of seeing sparse or orientalist representations of ourselves.

After watching the first two episodes, journalist Unzela Khan said she feels like her “day-to-day reality (minus the superpowers) was finally being shared accurately and safely with the whole world.”

In an audience study I conducted on the Muslim superhero archetype as part of my doctoral research, participants of many different Muslim backgrounds indicated an eagerness to receive Ms. Marvel.

Respondents expressed relief at seeing Kamala as a unique three-dimensional Muslim superhero in American comics, because she is a break from the relentless terrorist and oppressed women tropes entwined with representations of Islam that have dominated the western popular culture landscape.

They regard her as “relatable” because she connects both to her ancestral culture and American one.

The South Asian Muslim participants in particular were excited for her because she not only embodies much of their customs, but because she represents a break from the “Muslim equals Middle Eastern” portrayals. Black Muslim participants voiced this last point as well.

Refuge from stereotypes?

While most participants in my study welcomed Ms. Marvel as a refuge from Islamophobic stereotypes, one stressed that if a Muslim superhero appeared in a story showing something that didn’t reflect Islamic principles, there would be a risk this could negatively affect the Muslim community.

Since the show launched, some Muslim fans were outraged by Episode 3’s revelation that Kamala is a djinn. According to the Encyclopedia of Islam, a djinn is a Qurʾānic term applied to bodies composed of vapour and flame. Djinns are popularly understood as supernatural beings. The djinn filtered through a western orientalist lens has been a staple of orientalist “genie” depictions.

Many have said that it was a baffling choice to draw on orientalist tropes while making the first Muslim superhero in the MCU a djinn — and that they can’t cosplay as her now. The plot turn of Kamala-as-djinn isn’t in the comics.

Turning point of representation?

In my audience study, a young Indian Muslim woman was excited to see Kamala take over the Ms. Marvel mantle from her blonde and blue-eyed predecessor, Carol Danvers.

She said Kamala would let young, brown and dark-skinned girls know that they too were special after a lifetime of not seeing themselves represented in western popular media.

The Pakistani American Muslim illustrator, Anoosha Syed, recently tweeted about this in response to questions on Kamala’s identity, writing: “Seeing a lot of people online … angrily commenting ‘who is this show even for??’ Hi! Hello! It’s for me!!! ME!!!! A Pakistani Muslim girl who has literally never seen herself represented in media like this before!!”

https://twitter.com/foxville_art/status/1534566804206637057?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1534566804206637057%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_c10&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Ftheconversation.com%2Fwhy-ms-marvel-matters-so-much-to-muslim-south-asian-fans-184613

With the Ms. Marvel series currently clocking in at a 96 per cent positive rating on Rotten Tomatoes, I question whether we are on the cusp of a turning point for Muslim representation in the West — especially for South Asian and Muslim girls.

In the past, some dressed up as the orientalist Disney character, Princess Jasmine, for Halloween. With Ms. Marvel and other superheroines, girls are gaining heroines to choose from.