Category Health & Well-Being

TMU approaches health and well-being research by focusing on quality of life and promoting well-being for all.

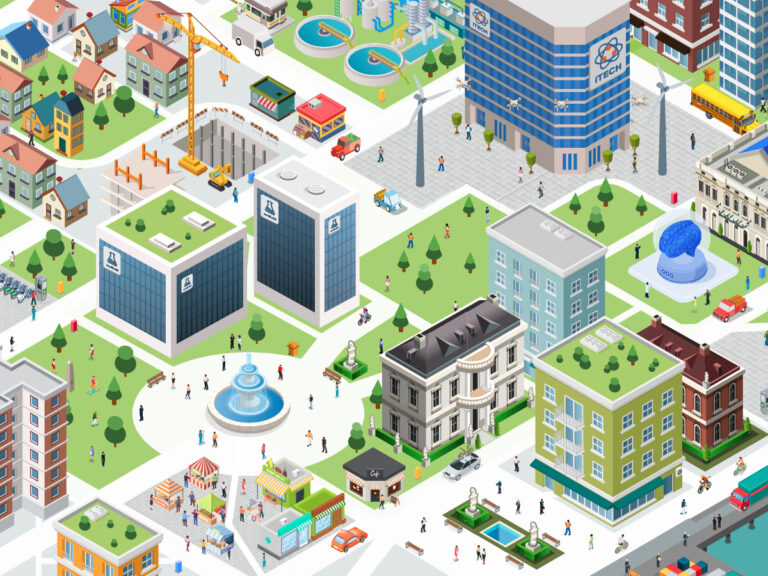

Mapping Ryerson’s COVID-19 research

Distance learning: How to avoid falling into ‘techno traps’

What pro sports should learn from resilient women athletes post-pandemic

Kids will need recess more than ever when returning to school post-coronavirus

Here’s why you’re craving the outdoors so much during the coronavirus lockdown

Coronavirus crisis shows ableism shapes Canada’s long-term care for people with disabilities

Conspiracy theorists are falsely claiming that the coronavirus pandemic is an elaborate hoax

During coronavirus hospital surge, a midwife recommends home birth

Coronavirus: For the sake of athletes, it’s too soon to cancel the Olympics

MDMA-assisted couples therapy: How a psychedelic is enhancing intimacy and healing PTSD