Category Justice, Equity & Society

Increasingly, democratic states and institutions are facing a combination of external and internal challenges. These challenges, impacts, and intersections are taken up by our faculty.

Colonialists used starvation as a tool of oppression

The stakes could not be higher as Canada sets its 2035 emissions target

As Erdoğan hints at retirement, how has his rule shaped Turkey?

Immigrant women suffer financially for taking maternity leave: 4 ways Canada can improve

Navigating special education labels is complex, and it matters for education equity

How audience data is shaping Canadian journalism

Renewable energy innovation isn’t just good for the climate — it’s also good for the economy

Use of lockdowns in Canadian prisons could amount to torture

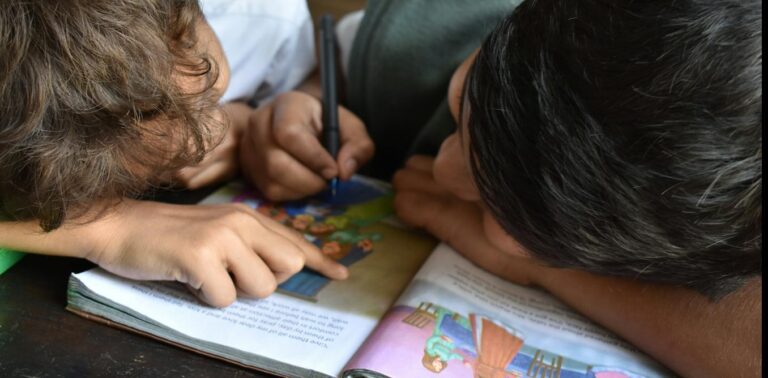

Schools have a long way to go to offer equitable learning opportunities, especially in French immersion

Why universities warrant public investment: Preparing students for living together well