Category Technology & Intelligent Systems

Working with industrial partners, TMU is creating a strong technological and industrial ecosystem through our research in engineering, design, management, and production.

OpenAI’s new generative tool Sora could revolutionize marketing and content creation

The first Neuralink brain implant signals a new phase for human-computer interaction

Bike and EV charging infrastructure are urgently needed for a green transition

The shift from owning to renting goods is ushering in a new era of consumerism

ChatGPT and Threads reflect the challenges of fast tech adoption

Enhancing survey data with high-tech, long-range drones

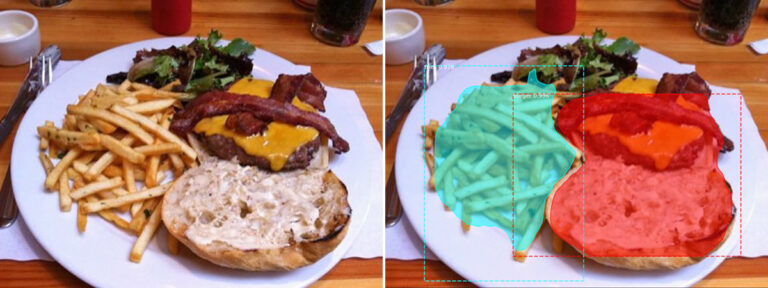

Counting carbs with AI for real-time glucose monitoring

Apple’s new Vision Pro mixed-reality headset could bring the metaverse back to life

Smart wearables that measure sweat provide continuous glucose monitoring

Gen Z goes retro: Why the younger generation is ditching smartphones for ‘dumb phones’