Category Culture & Creativity

Art and creative expression expand the ways we think about the world and our place in it, enrich our lives, and help us arrive at creative solutions to real-world problems.

Bottom-up, audience-driven and shut down: How HuffPost Canada left its mark on Canadian media

Why toy shops — and Amazon — are tapping into paper catalogues

Adele’s ‘30’: A mathematician explores number patterns in album titles

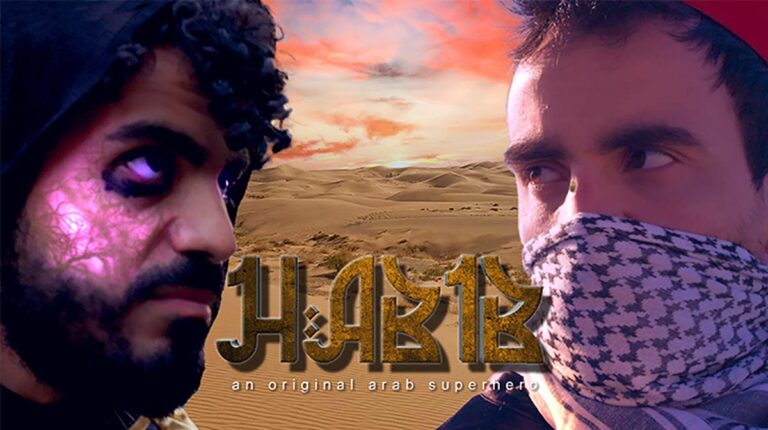

‘Habib’ spoof trailer uses pita bread weaponry in comedy arsenal to combat Arab stereotypes

Fewer viewers, nervous sponsors: The Olympics must rethink efforts to stay relevant

Game on! The opportunities and risks of single-game sports betting in Canada

Chinese American actresses Soo Yong and Anna May Wong: Contrasting struggles for recognition in Hollywood

Skepticism, not objectivity, is what makes journalism matter

How to help artists and cultural industries recover from the COVID-19 disaster

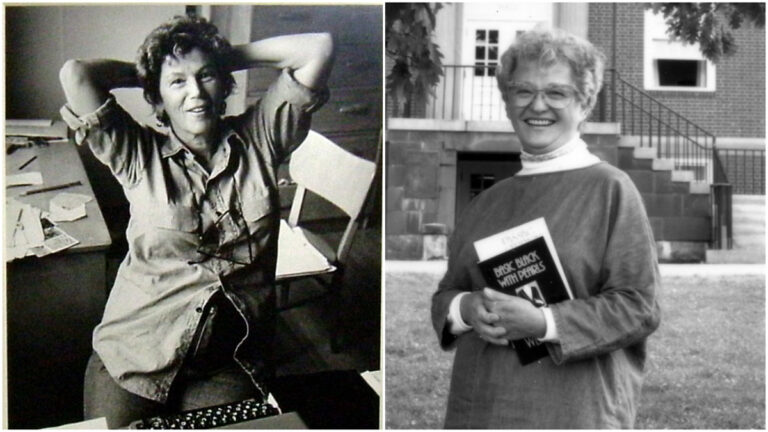

Daring reads by the first generation of Canadian Jewish women writers